Q&A with Kathleen Lenski, Author of "The Daughter of Vladimir Lenski: Memoir of a Child Prodigy Violinist"

Kathleen Lenski grew up in Los Angeles, California, in the 1940s and ‘50s as the daughter of two violinists who made sure she also became a violinist. She began performing in public at the age of three. When she was just twelve, she became a performing member of the first Heifetz Master Class at UCLA. Later graduating from The Juilliard School, a performing arts conservatory in New York City, Kathie spent her early adult life touring the world with her violin in various accomplished quartets, orchestras, and symphonies. In 2001, with the Angeles String Quartet, she won a Grammy Award for Best Classical Chamber Music for a recording of the Complete String Quartets of Joseph Haydn (68 Quartets in total) for Philips Classics. She played on 525 film soundtracks. You can read Kathie’s extensive musical biography HERE.

Kathie retired to the Central Coast of California, where I live, and we met in 2020 shortly after she began writing her life stories. While Kathie had never written before, she correctly realized that her life contained intrigue far beyond her impressive musical accomplishments. Kathie’s father, Vladimir Lenski, the man who groomed her as a child prodigy from birth and put her on the path that eventually led to success and happiness as a professional violinist—that same man had fabricated his own biography and lied to his family about it. He hadn’t been born to a Russian father and an English mother, as he claimed; he hadn’t toured Europe and Russia as a child prodigy violinist; he had never played for a Count who gifted him a famous violin. No, in fact, Kathie’s father was named Robert Saunders at birth and grew up in Paola, Kansas. He turned to teaching private violin lessons after his career as a performer never launched. Kathie’s mother only learned the truth about her husband’s origins and given name after Robert/Vladimir suddenly died when Kathie was just seven years old. Kathie didn’t learn the truth until she became an adult, and even then, her mother swore her to secrecy.

In The Daughter of Vladimir Lenski: Memoir of a Child Prodigy Violinist, Kathie examines the pieces of her extraordinary life, the smooth pieces and the jagged pieces, the pieces she chose and the pieces forced upon her. Read on for a conversation during which we discuss what Kathie discovered about her writing voice, how documenting her stories helped her process some of the more painful parts of her life, and what working with Kindle Direct Publishing was like for her.

QUESTION: You were just starting to tell me how this book came about.

KATHLEEN LENSKI: I was on the phone with a friend of mine who I mention on the first page of the book, the Acknowledgments page, an old girlfriend from teenage years. She played violin at the time, and we just clicked and remained friends for a lifetime. We started telling stories, and she was very good at asking questions that brought up memories for me, mostly about way back when we were teenagers. And suddenly she started to say, Okay, you've got to write this stuff down. And I was like, Oh, are you kidding? That’s so much work, no way. And she said, But what about your family? They want to know more about your life. So, I thought about that. And then the COVID shutdown happened. That's when I actually started writing things down. It would just be a story here and there that would suddenly pop up into my memory. Sometimes I didn't remember the stories correctly, but luckily, I had people that I could call, friends in Los Angeles who were present at the time when the stories happened.

Did it ever happen that you got somebody's take on a memory, and you didn't think that their memory was the stronger one?

No, no, I don't trust my memory. And I put that in the book right away. I said, I can’t promise you that my recollections are all accurate, but I tried my best with my aging brain. Please forgive me.

Had you ever written any of your life stories before you started writing this book?

I've never written anything. I've gone to therapists along the way, you know to help me get over my father's death and blah, blah, blah. All the troubles I had with my mother. And every time I went to a therapist, they would say to start a journal, to start writing things down because it will really help you. And I'd say okay, all right, try, and never last very long because I was bored with it. I just couldn't stick with it. So now I look at this book and it's like a whole lifetime of journaling, boom, all at once in three years.

What do you think it was that motivated you?

It was coming from somewhere outside of me, because some of the stories would just suddenly appear in my mind. I'd be out somewhere, at a doctor's appointment or something; I'd be waiting in the waiting room and have to find a piece of paper and a pencil and start writing it down, and then I'd come back to it later and be quiet and thoughtful and really try to make it into a story. Sometimes it just took me over.

If you didn't have a writing practice before this, how did you make space in your life and your schedule to work on it?

Now that I'm retired, and since with the neck injury I can't play at all, I've found other things to fill up my time. But again, this happened during COVID, and so I thought, Well, if there's ever a time to sit down and do this, this is the time.

What was the greatest challenge in getting this book from the first story to publication?

There's my computer illiteracy, if that's the right word, because I'm terrible with the computer. I wrote all my stories in emails and sent them to myself. I still don't know how to make a Word doc or a PDF. I would print all my stories out when I finished them because I needed to look at them in that format. It was even hard for me to read them on my computer. It's like it didn't quite make sense to me until I looked at it on a piece of paper. That's how old-fashioned I am. So finally, when I had all the stories together, I took it to my friend David Hennessee, who's a lecturer of English at Cal Poly, and he's also a professional violist. When I moved here and I was still playing, I actually played some concerts with him. I called him and asked him if he would be the editor. And he said, Sure, I'll take it on, not having any idea what kind of writer I was. It only took him two months. He whizzed through it. He liked the fact that I was writing for both musicians and nonmusicians. He really understood that because his life is like that: he's working with English major students all the time who know nothing about music necessarily, and then he has a whole world of musician friends here in this area.

Could you talk a little more about that? Did you know that you wanted to write both for musicians and nonmusicians? How did you think about your audience?

I started by thinking I was writing for the nonmusicians. And then I realized if this becomes a book, my musician friends are going to get ahold of it, and so I'd better start thinking about them as well. Especially when I got into details, stories of a certain event, I had to explain it to both of those categories.

How did you stay motivated to keep writing?

I went in and out. I'd have to take a break sometimes for a few months. And then somehow, all of a sudden, a story would come up, and I’d think, Well, better write that down. So, pretty soon I had a lot of stories.

Did you have to take a break because you were bored or because you were overwhelmed?

Overwhelmed. And then the whole time I was wondering what order to put these stories in. In the end it made sense to do it chronologically. It was pretty easy to decide that I wanted to start with the story of my father. But I was about two years into writing when my nephew on the Saunders side of the family—which is my father's real family—he got heavy into ancestry.com, and he sent me a disc that had all this information about my real father on it. At first, I got all excited. Oh wow, here's a lot of juicy stuff to put in the book. But after reading through it, I decided not to use it because none of it was true. This man, who called himself Vladimir Lenski, had a wild imagination. Just wild. He wrote a three-page biography when he changed his name—he had someone write it for him.

This was around 1925, maybe. He had all these stories in his mind, and he went to this woman writer who used that real flowery language of the time, and she loved those stories and just went to town with it. She created a story of how [using a sarcastic tone] Young Vladimir’s father took him to Europe because Young Vladimir’s mother was English and had a lot of connections in all the famous cities of Europe with famous violinists and teachers. But when you look into the history, most of those violinists were dead before this could ever have happened. This [false] biography went with a new birth certificate, a complete change of name [from Robert Saunders to Vladimir Lenski].

He moved from Los Angeles, where he wasn't making the career that he wanted, down to Anaheim. That's when my mother married him. She thought he was Vladimir Lenski. When he died, his sister came forth and told my mother, He's not Vladimir Lenski, he’s Robert Saunders, and this and that and this and that. The sister kept his secret until he died. So, here's this thirty-three-year-old woman with a seven-year-old daughter who could play the violin really well and was on this path that Vladimir Lenski was carving out for me. And it was going extremely well, it was what he wanted, and so she had a choice of whether to keep me on the path.

The information that your nephew was finding on ancestry.com, was that false information about Vladimir Lenski?

Yes.

That’s disconcerting, that ancestry.com could be so inaccurate.

Well, they found it [the truth]. He was born in 1890 in Kansas, and he died in 1953. Every ten years there was a census report about where he was, who he was married to, if he had a child. So, there were true things in there. And they also had the information that he had changed his name. So that was there. But they came up with newspaper articles about Vladimir Lenski, and this fabricated three-page biography, and things like that, which blew me away.

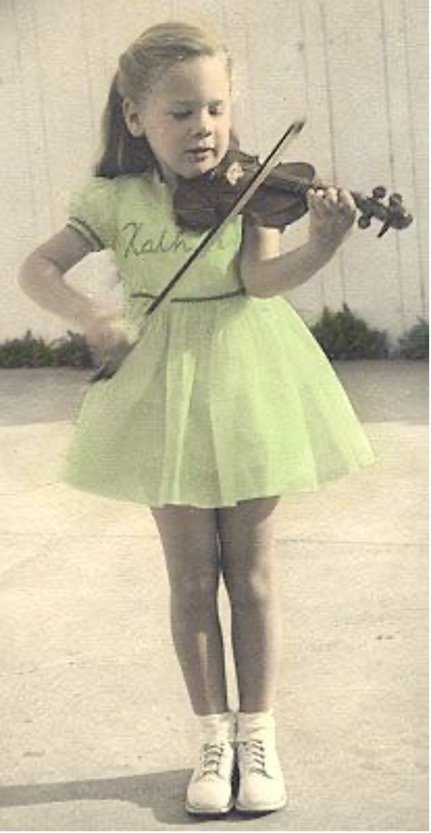

Kathie, age 4, wearing a dress made by her great-aunt Eva

“I don’t trust my memory. And I put that in the book right away. I said, “I can’t promise you that my recollections are all accurate, but I tried my best with my aging brain. Please forgive me.” ”

You mentioned that you got a lot of memories from the other people who were involved in your life stories, the other musicians and such. How else did you put together dates and things that you might not remember? Your mother saved a lot, right?

She was a scrapbook nutcase. And I continued to save the things that meant something to me, although when I moved from Los Angeles up here, I went through one of those phases of, I gotta get rid of this, get rid of that, and I got rid of too much. I regret some of the things I lost. But I kept enough to give me all the information for this book. I still have a lot left that I will eventually throw out. I tried to give as much as I could to my three remaining families—my stepdad is my third family. Oddly enough, of the three parents, I'm the closest to my stepdad’s family now. My Saunders family is on the East Coast, and the Stafford family is in Oregon. So, I sent those two families lots of paperwork and photographs and little dresses made by my great-aunt Eva, and things like that. Both of those families are working on family histories. The Stafford family on my mom's side has traced back to 1610 in England, in the town of Staffordshire. One cousin of mine is really working hard. There's one missing relative they're trying to find that connects all of us to the one in 1610.

This book is a real gift to both of your families.

Yes, it is, and that was a large part of the reason that I wrote it, for the Saunders family and the Stafford family. And then my cousins, who are my age, in my [step]dad's family in Ohio, they got really into the book and were so encouraging. They were constantly pushing me to, Keep going, keep going, we can't wait to see your book.

What was the most challenging part about the writing? Not publishing the book, but the writing.

I kind of fell right into the conversational style. I didn't know if I had a style, but that felt right. And I managed to remember a lot from my English education, English classes, so I did pretty well with that. It just all sort of came out. I was very conscious of not hurting people's feelings. That was a big one for me. Especially my second marriage, which ended very badly. I tried to write about it, and I threw away three or four different tries and finally decided, I can't write about this, it’s not appropriate.

I don't want to put words in your mouth, but I was wondering whether a difficult part of writing was dealing with some of the more emotional parts of your life and trying to figure out what to keep in and what to leave out.

Yes, that was tough. The second divorce was the toughest. And the other one that was really tough was about my group Musical Offering Baroque Ensemble. We were together for probably close to thirty years, but we had lots of problems. My divorce was one of them because my husband was in the group too. The fact that we were going through tumultuous times did not help the group. So, I decided to skip over a lot of stories that I could have told about that. But I wrote that: I said, I'm skipping over twenty years of some funny, some happy, some really unhappy, horrible, emotional things that happened. And then I checked with two members of that group to make sure it was okay that I even include that in the book. I sent them my chapters after I thought they were finished. And sure enough, these two people made some changes, and their changes are in the book

Changes so that you would give less information, or just factual changes?

Again, things that I didn't remember correctly.

How did you decide how to publish the book?

Well, I asked you for a recommendation, and you suggested [a local publisher], so I called him, and he said, Oh, sure, sure, I'll do it. He even gave me a price, but we didn't set a date. By the time I had made some progress and called him . . . his schedule had changed. He couldn’t even start until February, and we just got into February this week, so I would still be waiting. I happened to mention it to Gina [Watkins] one of the times that we were working with photos, and she said she could help with the publishing, and she did. It took a whole year.

You published it through Amazon.

It's called self-publishing through Amazon—it's Kindle Direct Publishing. They're not very expensive. I was surprised how reasonable it is to go through this process with them. Once they get all the information, you hook up with them and they start doing what they do on their end, they charge your bank account or they charge your credit card, and then when you order the finished book from them, they mail it to your house, and they put your profit in your bank account. That all happens automatically.

During the process, did you ever deal with a human?

No. That was a problem because I'm so computer illiterate, I had to depend on Gina. In fact, I was at her house yesterday ordering another thirty books at the author's copy price, which is half price, because I want to have them on hand for my two local bookstores, Coalesce in Morro Bay, and Volumes of Pleasure in Los Osos.

What would your advice be to another author who wants to self-publish in this way?

I would go to someone who does it professionally.

How many photos do you have in your book?

I think it's close to seventy.

They reproduced beautifully.

We went to AI for that. Gina knew about this program on AI where you can pay them $30 for one month and they’ll take as many photos as you give them, and they restore them. They'll take a blurry face on an old picture from 1940 and clear it up. It’s really amazing.

I noticed your book is selling for $21.50 on Amazon. How long will it take you to recoup your investment?

I'm not even interested in finding out. My mind goes blank with anything to do with math.

I'm wondering, for other people who might be looking to publish this way: Do you think it's possible that you will recoup your costs?

Oh yeah, definitely.

The scale isn’t outrageous? You don't have to sell 5,000 books?

No, no.

What kind of advice do you have for potential authors who feel they have a story to tell but haven’t ever written before?

Just start small, one chapter at a time. Just try to write what's in your head, and then maybe put it away for a while and come back to it and see how it strikes you. Then show it to somebody who's knowledgeable and could help you see what your natural style is. I've talked to people who couldn't imagine that they had a natural style, but I think we all do.

I liked how you said you discovered that your style is conversational. That seems true, but it takes a certain amount of confidence to even see that and recognize it and embrace it. A lot of people don't get that confidence piece. Maybe it helped that you're an artist. Did writing at first feel anything like when you first played music?

That’s a tough one because I started playing music so young. I don't have a concept of how music was for me in the beginning. I don't remember those first seven years, where my father was teaching me and getting me in a routine which stayed with me. I don't remember it. I can barely remember him.

Did it help to be in a writers group?

Oh, yes.

What about that was most useful?

Seeing what the other writers were going through and hearing their stories. It was nice to know there are all these other ladies my age who are writing stories about things that happened in my lifetime that I can relate to. Just watching them go through their process was encouraging. And when I'd read you guys a chapter, you'd all go, This is really good. I was very surprised by that.

I thought your first line, I am the daughter of Vladimir Lenski, and then your last line, And that is that, really worked as bookends. Were those sentences that you thought about and worked on for a long time, or did they just come to you?

I am the daughter of Vladimir Lenski was written like in cement in my head. From the moment I decided to try writing stories down, I knew that's what I wanted to call it. The other one came up as I was writing. There were certain phrases that kept coming up, and that was one of them. That one came up when I was writing about the things that my mother was always forcing me to do. I’d tell a story about something with my mother, and then I'd finished it with, That was that.

So that was your inner voice repeating itself, and you honored it by giving it the last word.

Yes.

In the book, the reader learns that your father made up a story about his origins. Did you ever wonder whether you shouldn't write that?

Yes. But at the same time, I felt that it was time for the world to know that he wasn't Vladimir Lenski. I had been keeping the secret for my mother. She didn't tell me about it until I was eighteen, and then she asked me to keep it a secret. Luckily, I had my own life to distract me right then, and I didn't really think it was that big of a deal. But much later in life, all those things change. Now I think it's a really big deal. I wasn't sure if I wanted to break my promise to her, but I had already started after she died in 1993. I started gradually, carefully talking about it to my close friends, that he wasn't Vladimir Lenski, and nobody fell over dead with shock, so I got more and more comfortable with it. All the time I was writing, I was looking up and wondering, Is there a heaven? Is there somebody looking down at me screaming, “I told you not to tell that!” I’ll just have to die and find out if she’s up there waiting.

At the same time, getting all this information from ancestry.com gave me a totally different perception of what she went through when he died. She turned against me, I was seven years old, and I didn't know what to think of any of that. What, he’s gone, he's never coming back? I went into a kind of fantasy world like Prince Harry [thinking about his deceased mother, Princess Diana], She's coming back, she's coming back. My fantasy world was, the front doorbell rings; I go open the door, and he's standing there. For years. I went into my whole little fantasy world, and I became very quiet, and I stayed very quiet for a long time. It took my whole lifetime to break out of that. So, this book is my big breaking out of that, telling the world who he really was, telling the world what my mother went through, telling the world that I broke my promise to her. But after all the rotten stuff she did to me along the way, part of me is saying, Why should I turn myself inside out at this time in my life? I deserve to be open even if she wasn't able to be.

I get the sense at the end of your book that there is a real sense of closure for you. Is that true? And if it is, did the writing process help bring you there, or do you think you were already there?

Oh, yeah, it was happening, but I wasn't thinking about it before I started writing. Maybe some of these stories would come through my mind now and then, but I didn't allow myself very much time to sit with it. But once it was written down on paper, that's the therapy part. And then when you're editing, you have to go over and over and over. I couldn't believe the number of times I had to read those stories! And there are still mistakes in this book, and I can tell you exactly where they are!

When I came to the “With Gratitude” section at the end, that's when that started spilling out. I felt the need to say, Thank you, Vladimir Lenski or whoever you are, for doing what you did for me. Thank you, Charlotte Stafford. Because I wouldn’t have this life if they hadn’t done those things for me. [Becomes emotional] And then there’s this part: I can't get past the crying. Am I ever going to get past that? This book brought up all these tears that were stuck in there. I was telling that to the ladies [fellow life story writers] at lunch. They've all experienced that, too, during writing. We all have stuff that’s really stuck, and it wants to come out.

Are you kind of glad it's getting unstuck?

Oh yeah, I am, but it’s embarrassing, like when I cry while sharing my stories during class.

I understand why it’s embarrassing, but it happens all the time. Maybe less so in morning classes when people are caffeinated [laughs], but people cry while sharing their own stories all the time—and sometimes we cry at each other’s stories. Just know that crying in a life story writing class is really, really common.

That makes me feel better.

I have a philosophical question about how connected we are to the stories of our lives as we're living them, and to the stories we’re told about who we are. You became this world-class violinist. How much of that do you think transpired because you believed that you came from a world-renowned violinist? If you had known earlier in life that Vladimir’s history was fabricated, do you think your life would have unfolded differently?

That's a great question. For most of the time, I was too young to even think about that. I didn't have much else going on in my head, other than music, while growing up. I jokingly say that to people now, concerning my inability to deal with math and numbers and money. I just couldn’t care less about those things, and I always say, Well, you know, it's because I have all those notes in my head. From a lifetime of memorizing music—it’s all still in there. That stays in there. Like, if I hear a little snippet of a certain violin concerto on the radio, and then I have to turn off the radio for some reason, the violin concerto keeps going in my head. That's because of how we learned to memorize.

There was an exercise we would do that's very meditational where you close your eyes, you get in a quiet place, make sure you're not going to get interrupted, sit there with your hands in your lap—not the violin in your lap—close your eyes, and visualize the motions of your hands moving. You go through everything in slow motion, so you have a picture of it, you have this recording of it in your brain: whether you're going to go up or down with the bow, whether you're going to go with this string or that string, with this finger or that finger, and every little tiny detail. You start and go all the way to the end, and it's like a tape recording going in your head for when you're in the performance. Then, when you're standing there in front of the orchestra, if you have a memory slip the tape keeps going so you don't fall apart and stop and make the whole orchestra stop and start over again. You see that happening sometimes in concerts. It's so embarrassing for everyone, and then often the soloists will get so freaked out that they start again, and they come to that spot, and it happens again. I've seen it happen three times in a row, where I was in the orchestra, thank God, but I felt so bad for my friend that this was happening to. So, I've got all those tapes in my mind. I played hundreds of concerts. Not always from memory, but still, even the ones that weren't from memory are in there somewhere, and hearing it on the radio starts off the tape.

So, it doesn’t sound like knowing Vladimir Lenski was living under a fraudulent name and history would have changed your life’s trajectory. It sounds like your story would have been your story regardless of his.

Yes, I think so.