Q&A with Deborah A. Lott, Author of "Don't Go Crazy Without Me: A Tragicomic Memoir"

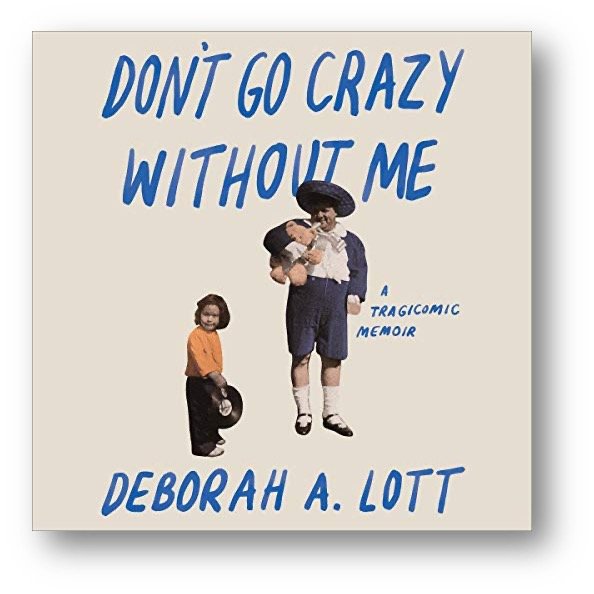

The following Q&A is from a 2021 conversation over Zoom between students from my Composing Your Life story classes and the memoirist Deborah Lott. We had all read Deborah’s raw, funny, painfully honest, meticulously written family story Don’t Go Crazy Without Me: A Tragicomic Memoir, in which she tries to answer the question, Am I destined to be like my father?

Deborah began by introducing herself, and then we took turns asking her questions.

DEBORAH LOTT: It was a long and winding road to publication because for years I was a closet creative writer. I was doing reportage, and I was writing for other people, and I was editing other people’s books and sometimes nearly ghostwriting their books, but I wasn’t really publishing my own creative writing. But I’d always kept journals, even from childhood. I finally went back to Antioch and got my MFA in Creative Writing, quite late in the scheme of things, and began to publish short pieces of memoir, pieces of flash fiction. I didn’t really think I had a book; I just had these episodes. It took quite a while before I started to shape a book that felt like it had a coherent beginning, middle, and end.

I was always in a writers group with really tough readers. I had taken a poetry course with Mark Doty, and he recommended an editor to work with who helped me to shape a coherent narrative. I’m not really a plot person, I’m more of a language person. I’m more of a poet pretending to be a memoirist.

And then pretty late in the process I decided to add the present-day episodes that are interspersed with the coming-of-age story. And I did that because I realized that one of my big concerns as a human being is how the past continues to reverberate in our lives, how those memories come back, and when those memories come back—and what we get over, and what we never get over. So, I wrote those present-day stories pretty quickly and then had the dilemma of where to place them so that they would have their own arc.

QUESTION: How did you deal with family members? How did you keep them in mind while you were writing?

I tried to always write with compassion. I would take the point of view of every character and not turn anyone into a villain. Sometimes we write a first draft that’s sort of a therapy draft, where we can just write for revenge. We can write, Why me, why me? We can feel like a victim, but that’s not the draft we’re going to publish as a book. My parents are both dead, which I think makes it easier because I didn’t really have to think about what their reactions would be, although when I was publishing and my mom was reading my work, she was always encouraging and never was upset by the way she was portrayed.

I have two brothers who are both in the book under slightly different names, and neither one of them chose to read the book. One brother says, I lived through it, why should I have to read about it again? The other brother says, I don’t remember anything, you probably made it all up.

I did not share the book with my cousin [who appears in a scene from Deborah’s early life in which the two of them engage in sexual experimentation]. I don’t know whether he even knows I wrote it. I don’t know how he would feel about it.

The only members of my family who have actually read it for sure are my two nieces, who have been really supportive and nice.

Did you know that your brothers wouldn’t want to read it when you were writing? Did you write it as if they might one day read it, or did you feel they had given you license to tell your own story?

I figured it was my story and they could write their own versions. I thought that they might read it, but I didn’t think they came off badly or that I was revealing any of their secrets.

Also, this is what I tell my students: you kind of have to be ruthless to be a memoirist. I don’t know that you can justify it on absolute moral grounds. Just like how Janet Malcolm, who recently passed away, talked about journalism. Of course it’s your version of events, of course you’re the protagonist in your story, of course other people would see it a whole other way. In every family, every sibling has their own childhood, even though you have the same parents. So, I think there has to be a certain ruthlessness. You just say, I’m going to write this. I can’t help it, this is what I do. If I offend you, please forgive me, but this is what I do.

But I think write with compassion. Don’t write with vengeance in mind. Don’t write to get back at anybody. It usually doesn’t work. What happens is the reader will usually identify with whoever you’re out to get and decide that you’re a terrible person. It’s just a reflex in readers, that if you come down too hard on anybody, they will start to defend whoever you’re coming down on.

In our life story writing classes, some writers choose to write all the nitty-gritty about family members and other people in their lives, and some choose not to.

Yes, I think it’s a decision that you make, and you make it over and over and over again about everything you’re writing and who you’re writing about. And it’s not easy.

Could you talk about how you seem to remember events that happened much earlier in your childhood than most people tend to remember?

I remember things that happened early in my life a lot better than I remember what happened yesterday. I also kept journals, so some of these childhood events I wrote about over and over again starting when I was just a teenager. So that helped. Dialogue, of course, is reconstructed. I don’t remember exactly what my parents said in every one of those scenes. You’re reconstructing it from what they always tended to say. I do remember my father saying, This is your first death—there are certain things I do remember very specifically.

You compress time—that’s part of what you’re doing creatively. There are two significant car accidents I was in with my dad, and I only chose to write about one of them, and I have it stand in for both of them. It’s not reportage. If I were a reporter, it would be different. When I was writing about Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination, I did feel like I needed to be absolutely true to the facts. I made sure that I did the research, and I tried to contact other people who were there at the time, and I looked at a lot of old TV footage. I went to the UCLA TV archives, shut myself up in a room, and watched a lot of old archival footage to make sure that was accurate.

I talked to my brothers as much as I could about some of the early childhood memories. One brother has an incredible memory, so he helps me fill in.

I wouldn’t take it to the bank that everything is factual in the way that a reporter in a newspaper needs to be factual, but all the major events actually happened.

How do you define creative nonfiction in the sense that it’s mentioned on the cover of your book [on some copies]?

I think creative nonfiction started with the new journalism, with Tom Wolfe and Gay Talese and people who wanted to bring the reporter more into the story and felt like writing a completely objective story was impossible. That was probably the genesis of creative nonfiction. Then it moved to writers saying, Why can’t I use some of the techniques of fiction in writing nonfiction? Why can’t I have more dialogue, more scene-making? In terms of memoir, it’s really trying to shape it as art. Not just trying to report what happened, but to make something artful out of it. How do you pay attention to language in the way a poet or novelist would pay attention to language? How do you create scenes, as opposed to just telling what happened? So, a lot more “showing” than “telling.”

The term is constantly being redefined as writers push the boundaries. Nick Flynn wrote a memoir called Another Bullshit Night in Suck City, and he actually goes inside his dad’s head and writes some scenes as if he were his dad. There’s a lot of creative license there.

When you were a teenager in the book, you made a conscious decision not to “go crazy.” You chose feeling but not your dad’s hysteria. After that decision, did some of the symptoms you’d had previously and shared with your dad (like hypochondria) dissipate? Where did it go from there?

I was obsessive compulsive—I was doing a lot of compulsive behaviors, and I started to resist doing those . . . But many, many years of therapy followed. Am I still a hypochondriac? Yes, my family was on [the radio program] This American Life as a family of hypochondriacs. My husband still wants to run out of every family dinner because my brothers will start talking about their symptoms. They start at the top of their heads and work their way down their bodies, and it will drive my husband to distraction.

There is a lot of mental illness in my family, and of course it’s biologic. Thank God for meds. Thank God for meds. I would never want to say, if you’re bipolar, if you’re schizophrenic, you can talk your way out of it. But I felt like I was on a precipice where I could choose to go where my father had gone, to just believe everything he had believed, to believe that the universe was a dark and dangerous place. And when I made a decision that it was okay to have emotion but that it didn’t have to be his version of emotion, I think I started to feel better. But lots and lots of therapy. And am I still crazy? Yes, kind of. But, on a good day, not psychotic. [Laughs]

In your interview with the Los Angeles Review of Books, you made the point that any story could be told five different ways. How did you make your choices in the way you told stories?

I actually wrote a lot more stories than wound up being in the book. I have drawers full of them. I was looking for milestone moments, or touchstone moments, or moments that were the most vivid to me. [And times] that seemed to be turning points in the family, too. I was trying to figure out how the decline of my father really began, and then I traced it back.

I think for every book you wind up writing a lot more than you use. The editor I was working with was all into narrative momentum, and keep things moving, and keep the reader wanting to read on, don’t get bogged down.

It sounds like there’s a lot of instinct involved in deciding what moves the story forward.

Yes, you get a sense of momentum and what the story really is. At a certain point I had a big whiteboard—I had timelines of my family, I had timelines of what was going on in society at large during different years, and then I also had a thematic board. And I had one big shaping question: Am I destined to be like my father? I felt like everything had to be sort of answering that question. And, if I’m not going to be like my father, who am I going to be? A lot of memoirs start out with a guiding question, or at some point in the writing process you go back and ask, Okay, what is the big question?

And then I also found as I was writing that there were natural metaphors. Like, the color aqua kept coming up. It was the walls of our living room, and then it wound up being the color my father painted all his ceramic ducks in the mental hospital. I have one. I said when he gave it to me in the book that I gave it back, but in fact, after he died, I wound up with them again. I have it on my desk, a little memento. So that color became a natural metaphor. You think about themes, metaphors, what’s going on at the level of language.

Are you saying you wrote that question at the top of your whiteboard: Am I destined to be like my father?

Yes. I’ve looked at some other memoirs, at what their guiding question is. For example, I don’t know whether anyone has read Jody Forrester’s book, Guns Under the Bed: Memories of a Young Revolutionary, which I highly recommend. Her question, as I read it, was, How did I go from a headstrong, willful young girl alienated from my parents to a member of a radical leftist organization where I was willing to die for the Maoist cause? And, how did I get out? How did having that experience change me?

Melissa Febos—I don’t know if anybody has read Whip Smart: The True Story of a Secret Life, which I also recommend. In an article in Poets & Writers, she said that her guiding question was, How did a girl from a loving family end up shooting speedballs and spanking men for a living? How did the power of secrecy become a prison?

I do think it’s really helpful to come up with a question, or two questions, or three questions—probably no more than four or five—and see how the book shapes itself around the questions.

“you kind of have to be ruthless to be a memoirist. I don’t know that you can justify it on absolute moral grounds.”

There’s a part in your book where you said how important your relationship with your cousin, your high school friend, and your writing was to maintaining some sanity during a difficult part of your life. I wondered if you could speak a little bit about how your writing did that for you.

I think it kind of saved me. I think it saves me every day. The days that I don’t write I start to feel crazier and crazier. It just organizes—it organizes your thinking, it organizes your experience, it gives things a beginning, a middle, and an end when they feel like they’re spiraling all over the place. I think that human beings are meaning-making creatures, and it’s a way to make meaning. Somebody said, The worst place to think is inside of your head. It’s much better to think on the page and try to get some clarity. And also, then you have something. I have the same relationship to cooking, where if I can cook, I feel much saner. If you can shape something . . . Even if you never publish, even if you feel like what you’re writing you’re never going to share with anybody else, I still think there’s value in it.

In terms of psychological impact, there’s a guy named James Pennebaker who’s studied the psychological effects of writing and that it’s good for people. For the most part, writing about trauma, writing about upsetting events, is good for people. It calms down the nervous system. Unless you really don’t want to do it. But if there’s some part of you that wants to do it, usually it’s good for you.

Did you find catharsis from finishing the book?

I think I did, but I also felt like I still want to keep writing about these episodes—what’s wrong with me that I still keep wanting to write about these and looking at them from different angles?

And then you start wondering, Now how am I going to get this published? That was a grueling process. First, I had a New York agent, and she was going to all the big [publishing] houses, and they said, What are we going to do with this book? We don’t know how to market this book, we don’t know who’s going to read it, this person doesn’t have a big platform, she’s not famous, does anybody really care about the story? That was really disheartening. It’s like you get a moment of catharsis, and then you get the impact of the commercial world of publishing. I was lucky ultimately to find a small press, Red Hen Press, that’s based out here [California], where the founder, Kate Gale, who’s also the editor, just really got it and wanted to publish it.

One thing that comes through is that yours is a story of survival.

For sure. A lot of people come through worse. Working with the National Center for Childhood Traumatic Stress, what you learn is that, in the nature of human history, trauma is not abnormal. Trauma is the norm. Most people live through wars and genocide and plagues. That we’ve had such privileged, safe lives is not the norm. It’s an aberration. Just realizing that, we’re all survivors, right?

If you write a story with the intention of publishing it, does that change the way you write it?

I was hoping it would be published, but I didn’t really think of anybody reading it. I didn’t really think about the impact. I did an interview right after it was published with a woman who wanted to talk about all the mental health issues, and I thought, Oh my God, what have I done? What have I put out there? I must still be crazy to have done this. I don’t think you can change the way you write to appeal to a commercial audience. That’s never a path to success because nobody can predict what’s going to sell from one minute to the next. The editors think they can predict, but they really can’t. There are always big surprises. I think you just need to write what you’re passionate about writing.

At what point in your career did you write the book?

I started writing it quite a long time ago. If I think about when I first published episodes that wound up in the book, it’s like twenty years. When I first conceptualized it as a book, I was already in my fifties. I didn’t go back to get my MFA until my fifties, so I was a closet creative writer for a long time. I think you have to be a grown-up to write memoir. I don’t think you can write it while you’re going through it. It takes years of reflection.

You said you had lots and lots of therapy. Did you think about including that, to show people how you got to the other side?

I didn’t really think about including therapist sessions [aside from the two she does mention in the book]. I feel like that opens so many cans of worms, and I guess I don’t feel like you “get to the other side.” Every day you’re deciding, How sane am I going to be today? How rational am I going to be today? How am I going to function today? How good a person am I going to be today? I’m in therapy again now. I hadn’t been in therapy for probably twelve or fifteen years. My husband is going to have heart surgery, which is a big trauma looming over me, so I decided maybe I need to go back to therapy and talk to somebody and not burden my husband with some of my stuff. I guess I don’t think about it as getting to the other side, just doing the best you can every day.

I went through a long period of feeling like I should be able to write myself out of my troubles. And that has worked during many phases of my life, but it didn’t work during my most recent rough patch. It took me years to realize that my writing wasn’t curing me. Do you ever have a hard time recognizing that line, where you can’t write yourself out of something but need additional help?

I have kind of an ambivalent relationship with therapy because I’ve had some bad therapy, too. I’m actually a volunteer with an organization called TELL, where we help mostly women who’ve had bad experiences in therapy take action and take their power back. So, I don’t think therapy is always the answer either, but sometimes you just need a sounding board. If you don’t want the writing to just be for you, if you’re trying to create something for other people, it can’t just be therapy, either.

I don’t think you can cure yourself just with writing or art. There wouldn’t be so many artists who are so mentally ill. The artistic temperament is not an easy thing to live with. That’s just the truth. If you’re sensitive and you’re a writer or you’re an artist, you suffer a lot. You take things hard.

Your process probably changes with the project and what’s going on in your life, but could you talk about what your ideal writing process is, to actually get work done?

I think it helps to be in a writers group. I’m in a writers group now where we’re tough on each other and we give each other deadlines. You need deadlines or you need assignments. It helps me if I have a pretty good idea that something I write is going to go somewhere. Readers. Having readers along the way who can say, This is working or This isn’t working. And having some kinds of audience so you’re not just working in a void.

I’m not a super disciplined writer. I’ll write one day for like twelve or sixteen hours straight, and then I won’t write for three or four days. So, I’m not a role model. Don’t write the way I write. Have a regular daily discipline, do morning pages, say you’re going to write 1,000 words a day. Do it the way everybody, like Stephen King, tells you to do it. Don’t do it the way I do it.

Regarding getting feedback from other writers, constructive criticism can be hard to hear. And then it can be difficult to decide whose reactions to care about. Can you talk about what that’s like for you in your writers group, if you share something and five people have five different opinions? How do you deal with it emotionally, and then how do you sift through responses?

That’s a big question. At this point I’m in a writers group with three other people that I really trust and whose opinions I really value. But there are times when I’ll get a critique and it will really rankle me, where you can’t look at the notes for a little while. It’s tough. I teach writing workshops at Antioch, and we have rules . . . hear the notes, consider the source if you can, and then give it a little time to see what really rings true for you. Writers groups can be destructive, or they can be constructive. You have to find your readers, the people you’re really writing for.

It helps to empower yourself when you go into a critique group to ask what you want to know. So, if you’re not ready to hear everything, then say, What I want to know right now is where this character doesn’t feel authentic. Or, What I want to know right now is where the energy is lagging for you, or where this isn’t making sense, or where you have questions, or where you need more.

Could you talk about the “notting” part, how you decided to put that in there? The rhythm of that part kind of made me nauseous.

It made me nauseous too! It was part of one of my compulsive rituals. I wasn’t allowed to write because this other girl had died, and I hadn’t died, and my father was going crazy, and I just decided I wasn’t allowed to write. It was a kind of penance where I would write something and then I would feel like I had to cross it out and write it a different way. Whatever I would write would feel like the wrong words, or I thought something bad would happen if I wrote it that way. Sometimes people who have OCD do “undoing” where they do something and then they feel like they have to undo it. I’ve seen a homeless guy who will walk forward and count his steps, and then he feels like he has to walk the same number of steps backwards in this torturous way. So, it was a form of undoing, but it was attacking my writing, which was the one thing that was kind of keeping me sane. It was terrible for me in school because I would be crossing stuff out on my papers, and the teachers would ask, What’s going on here? And just like with any OCD ritual, you just have to stop it. The more you do it, the more the loop gets reinforced in your brain. You’re deepening the neural pathways in your brain with the behavior, so you just have to stop it cold.

Is there a literary term for when a writer writes in a way that brings about a physical effect in the reader?

Lidia Yuknavitch talked a lot about “corporeal writing,” writing that’s deeply embedded in the body. And I talk about embodied writing with my students: you can’t get too far away from the body when you’re writing. If you get too abstract and too in your head, you’re going to lose your reader. You have to anchor everything in physical experience. We’re in our bodies. Even when we think we’re just up in our heads, we’re still feeling things in our bodies. But I don’t know if there’s a word for making the reader feel what the writer felt at the time.

When we discussed this book, there were two things that people appreciated most. One was that your present-day sections felt so important, and readers were really grateful for them because they acted as sort of a reprieve, and they answered questions that came up as we read. It’s also reassuring to be reminded, after reading about some of your trauma, that you’re alive. You survived.

Another one was the way you form words and sentences. There are some passages that are breathtaking. I would like you to tell us that that’s really hard, that it takes a lot of work, and that you don’t just wake up in the morning and have that poetry spill out of you. I mean, tell us the truth, but I’m hoping it’s the former.

Once in a while you get really lucky and something spills out of you that’s really beautiful, but most of the time it’s on the fortieth draft, and it’s reading aloud, and it’s reading a lot of poetry. I read a lot of poetry and pay attention to language. I think if you read your work aloud, you hear the rhythm of it and you hear whether the language is working. One of my inspirations is the memoirist Bernard Cooper. He started out as a visual artist, and then he became an incredibly beautiful writer where every word is just stunning. I took classes with him, and he talked about writing word by word, literally word by word, thinking about every word in a sentence and the syntax of the sentence and the structure of the sentence and the relationship of one sentence to the other and just how it feels in your mouth. Every time I read my work aloud, I change something.

So, no, it doesn’t usually come out like that. Occasionally you get on a roll, you get in the flow, whatever it is, God speaks to you—I don’t know what happens.

Will there be a sequel? Is that what you’re working on now?

I don’t know if it’s a sequel. I started working with the journal I wrote the year my dad died, and lot of it is about a relationship I was having with this guy, and my relationship with my sexuality. I was feeling pretty morbid and at the same time having a lot of sex, so it’s about that pull: Thanatos and Eros. I’m just not sure if there’s a book in it. I don’t see the arc yet.

You wrote about sexuality in Don’t Go Crazy Without Me in raw ways. I know there was humor in this book, but I felt like you didn’t rely on humor when you wrote about your body and its many functions. What were your boundaries when writing about your sexuality? It must help to have a spouse who isn’t threatened by that, or you wouldn’t be doing it—? [Bloggers note: Deborah’s husband was present for this interview.]

Well, I’m not writing too much about my sex life with him. He has said that if I write about my sex life with him, the rule is it has to be the best sex I’ve ever had. [Laughs] I just took a course with Garth Greenwell called “Writing About Sex.” Garth Greenwell wrote a book called What Belongs to You, and then he wrote another book called Cleanness, and then he just edited an anthology called Kink. So, he’s a big advocate of everybody just coming out there and writing about sex honestly and completely and not censoring ourselves; writing about physical acts the same way you would write about anything else and not considering it a taboo area. And that’s kind of where I am. I felt like the big taboo in my book was writing about childhood sexuality, that I actually masturbated as a child. I just think you’ve got to go for it, unless you decide that’s not your subject. Garth Greenwell says something like sexuality is a crucible of human interaction. You see everything there: you see personality, you see what’s going on in a culture and society, you see what’s going on in gender relations, you see people trying to work out childhood trauma and childhood relationships. There’s so much richness to pull from sexual experiences that if we forbid ourselves from writing about that, we’re cutting off an awful lot of human experience.

Do you have a last piece of advice for us, fellow writers of life story and memoir?

Send your work out, and if it doesn’t get accepted don’t take it personally. I’ve had pieces get published that were rejected twenty or thirty times. That’s just the nature of the beast. You don’t know who’s reading at the other end, and sometimes people just don’t get it.

For a taste of Deborah’s sense of humor, watch this short film she and an assistant made. It was a fun distraction, she said, during the period of time when her book wasn’t finding a publishing home.